Case Report

Invasive Mucormycosis Infection Complicating COVID-19: A case study at Benghazi Medical Hospital

1University of Benghazi, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Physiology, Benghazi, Libya.

2University of Benghazi, Faculty of Medicine, Department of pharmacology, Benghazi, Libya.

3Department of Biology, Faculty of Arts and Sciences-Gamines, University of Benghazi, Benghazi, Libya.

4 School of Veterinary Medicine, University College Dublin, Ireland.

5Telenostic Ltd., Kilkenny, Ireland.

*Corresponding Author: Nagwa Elghryani, Department of Biology, Faculty of Arts and Sciences-Gamines, University of Benghazi, School of Veterinary Medicine, University College Dublin, Ireland.

Citation: Faiza A. Elhamdy, Aisha M. Alfituri, Elghryani N. (2025). Invasive Mucormycosis Infection Complicating COVID-19: A Case Study at Benghazi Medical Hospital. Clinical Case Reports and Studies, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 9(4):1-5. DOI: 10.59657/2837-2565.brs.25.227

Copyright: © 2025 Nagwa Elghryani, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: January 18, 2025 | Accepted: February 01, 2025 | Published: February 08, 2025

Abstract

Reports of COVID-19-associated Mucormycosis have been increasing in frequency since early 2021, particularly among patients with uncontrolled diabetes. Glucocorticoid treatment, malnutrition and other immunosuppressive conditions might also enhance secondary infections. In this study, we are presenting a case of COVID-19 patient who she developed an invasive Mucormycosis infection. We tried to emphasize the importance of early detection of any associated pulmonary and or CNS fungal infection in COVID-19 patients by frequent sputum sampling and nasal biopsy and undertaking paranasal sinus and a follow up CT chest, especially for the progressively deteriorating patients with a predisposing factor.

Keywords: invasive mucormycosis; infection; complicating covid-19

Introduction

SARS-CoV-2 is the virus responsible for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). It causes a respiratory illness that can vary from asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic cases to severe bilateral pneumonia, leading to progressive respiratory failure because of extensive lung damage [1]. Systemic corticosteroid and immunological treatments can reduce mortality in people with the most severe courses of the disease. [2]. However, these treatments can predispose patients to secondary fungal infections. The most common fungal infections in patients with COVID-19 include aspergillosis and invasive candidiasis [3]. Rare mold infections, such as mucormycosis, are likely underreported [4-6]. Mucormycosis is a virulent fungus that commonly exists as a commensal in the nasal mucosa. However, it can become a highly aggressive and progressively invasive infection in immunocompromised states [7]. COVID-19 patients are particularly susceptible to mucormycosis, especially those in intensive care units [ICUs]. Additionally, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, glucocorticoid treatment, malnutrition, and other immunosuppressive conditions are considered predisposing factors for mucormycosis [8, 9]. Mucormycosis primarily affects the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses, presenting as acute sinusitis. In immunocompromised patients, it rapidly spreads to the orbital and intracranial regions, leading to progressively worsening clinical outcomes. [10-12]. Therefore, a high index of clinical suspicion, early diagnosis, and prompt aggressive management are critical for a successful outcome. Patients with suspected invasive mucormycosis should undergo urgent CT imaging of the paranasal sinuses and chest, along with endoscopic examination of the nasal passages. Biopsies of any suspicious lesions are essential for detecting this severe condition at an early stage, thereby improving the mortality rate.

Case Study

A 70-year-old female patient from Benghazi was admitted to the Amal Infectious Unit at Benghazi Medical Hospital, Benghazi, Libya, on February 6, 2021, with a diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by a positive reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test and bilateral basal opacities observed on chest X-ray and CT (Figure 1).

Figure 1: (A) Chest X-ray demonstrating bilateral obesity, more pronounced on the left side. (B) High-resolution CT scan revealing areas of ground-glass opacities and bilateral consolidations, predominantly located in the peripheral regions.

The patient was a known diabetic, managed with oral hypoglycemic drugs, and hypertensive, on Amlodipine and Candesartan. The patient also had a history of chronic sinusitis, bronchial asthma, and residual pulmonary fibrosis. The onset of COVID-19 symptoms, including pyrexia, tachypnea, severe breathlessness, and a sore throat, reportedly began 10 days prior to admission. During this time, the patient was managed as an outpatient with a regimen of corticosteroids, antibiotics, and a prophylactic dose of heparin. However, due to a deterioration in oxygenation (PaO₂ <80>2000 ng/mL), and an increased D-dimer level. A peripheral blood film report indicated thrombocytopenia and a clumped platelets phenomenon.

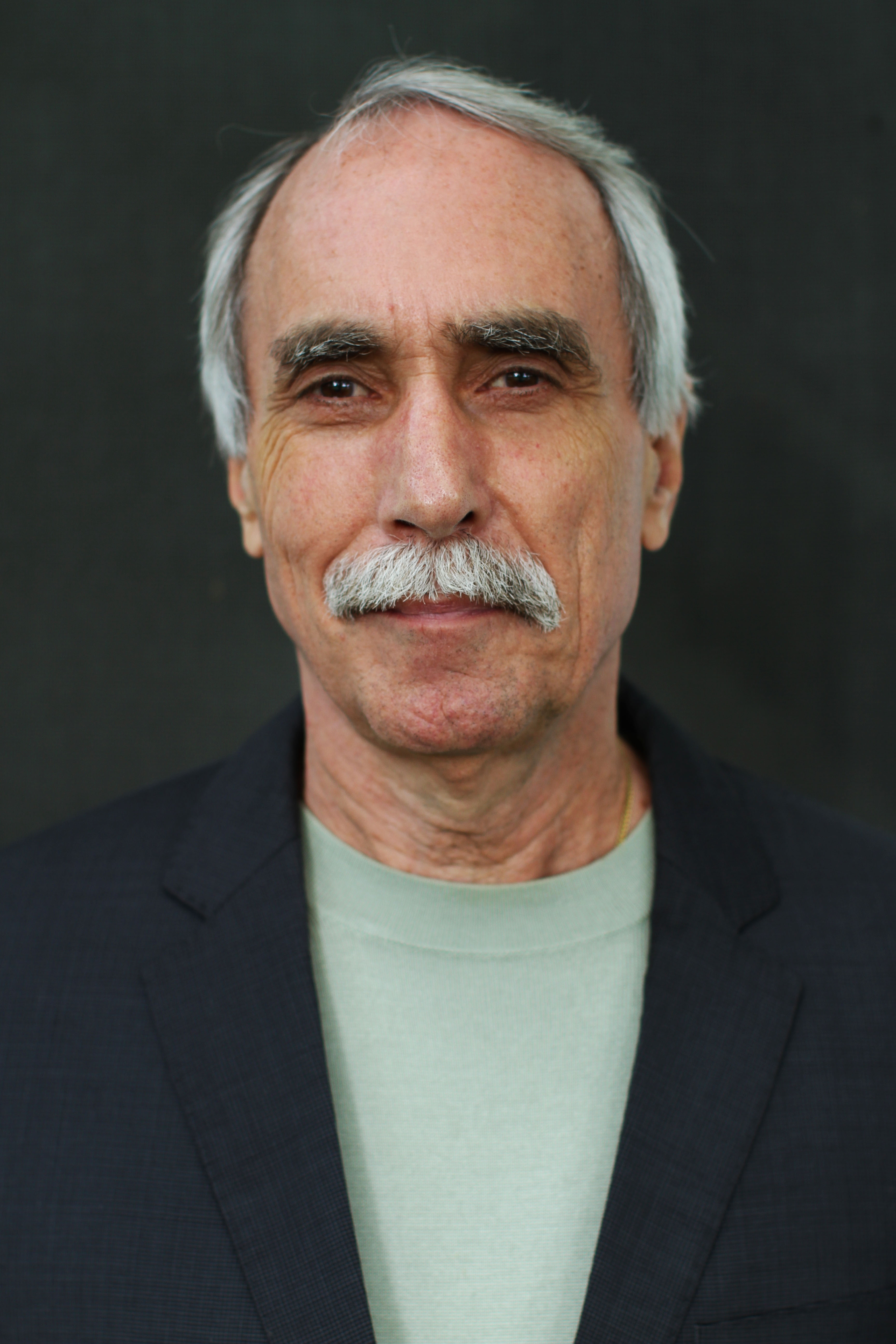

The patient was started on a therapy of intravenous methylprednisolone (1 g infusion), intravenous ceftazidime (1 g every 8 hours), and oral azithromycin (500 mg every 12 hours), along with oxygen administered via nasal cannula. Two days after admission, the patient’s condition deteriorated, with further reduction in oxygen saturation, necessitating transfer to the ICU. In the ICU, non-invasive respiratory support was initiated with a positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) of 12. The patient was switched to intravenous ceftriaxone, and oral azithromycin was administered via an orogastric tube. Intravenous hydroxychloroquine was added, with a loading dose of 400 mg followed by 200 mg twice daily. Heparin therapy was discontinued due to thrombocytopenia and haematuria. The following day, tocilizumab (8 mg/kg) was added to the previous regimen, along with intravenous ascorbic acid (6 g every 12 hours). Three days later, another dose of tocilizumab was administered. On the same day, the patient developed right-sided hemiplegia and motor aphasia, prompting the re-initiation of heparin therapy. The patient also developed bilateral conjunctivitis, proptosis, and discharge from both eyes, particularly the right eye (Figure 2).

Figure 2: perorbital odema and redness with black discharges

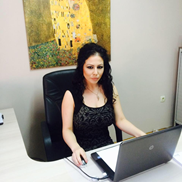

Her nasal examination revealed dryness with black crusts. The mucous membranes were also dry, with oral thrush and black crusts present in the oral mucosa. A biopsy of the nasal cavity was performed to assess for a possible mold infection, and the samples tested positive for mucormycosis. A CT scan was conducted (Figure 3).

Figure 3: A: MRI showing nodules and reverse halo sign typical of mucormycosis. B: Magnified picture showing magnifying finding of A.

On day 8 of admission, the patient's oxygen saturation further deteriorated, prompting an increase in PEEP from 12 to 16. The patient was placed in the prone position for 18 hours, and both antibiotics and hydroxychloroquine were discontinued. A loading dose of remdesivir (200 mg) was initiated. However, the following day, the patient's condition worsened. She required circulatory support with a vasopressor (norepinephrine = 0.2 mcg/kg/min), and her renal parameters began to rise. Treatment with intravenous liposomal amphotericin B (5 mg/kg) was started for 5 days. The patient's general condition improved, and there was noticeable improvement in gas exchange. However, two days after stopping the antifungal treatment, her condition deteriorated again, and she passed away on day 15 of her admission due to refractory shock and respiratory failure.

Discussion

Based upon the patient’s clinical presentation of sever covid-19 infection complicated with cerebrovascular accident, thrombocytopenia, respiratory failure and finally ended with death. The patient's scenario is due to pulmonary Mucormycosis superimposed COVID-19 infection and the CNS manifestation could be due to invasive fungal infection. The progressive patient's deterioration followed by the improvement following the administration of Amphotericin B in a COVID-19 patient with risk factors and the positive nasal biopsy and sputum culture for the mucor species made us thinking of the possible invasive Mucormycosis in a COVID 19 patient. The patient had history of diabetes mellitus, preexisting pulmonary disease chronic sinusitis and bronchial asthma. The patient had received high doses of Corticosteroids for prolonged period, Hydroxychloroquine, Tocilizumab and broad-spectrum Antibiotics due to COVID-19. Corticosteroids predispose to Mucormycosis by suppressing the immune system and by inducing hyperglycemia in prediabetics and diabetic patients. Based on the RECOVERY trial, Dexamethasone at a dosage of 6 mg once a day for up to 10 days is recommended for only hospitalized patients with COVID-19, who are receiving supplemental oxygen or mechanical ventilation [13]. Nevertheless, many patients with mild COVID-19 who are not requiring supplemental oxygen have been treated with glucocorticoids, and even with higher doses and for a longer duration. Certainly, misuse of glucocorticoids and failure to adequately control elevated glucose levels are considered to be the major contributing factors for invasive Mucormycosis.

On the other hand, Hydroxychloroquine is an anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive drug used for treatment of Malaria and various autoimmune diseases. So, by decreasing patients’ immunity, it can enhance fungal growth [14]. Moreover, COVID-19 infection induces a dose-dependent production of IL-6 pro-inflammatory cytokine from bronchial epithelial cells. Thus, Tocilizumab, a recombinant humanized anti-IL-6 receptor monoclonal antibody, which is an FDA approved drug, has been prescribed along with Dexamethasone. So, this drug reduces the patient's immune response and so increases the risk of Mucormycosis in post-COVID-19 patients [15]. Other possible contributing factor is the overuse of antibiotics. Antibiotics may suppress normal bacterial flora, allowing fungi to become established in the sinuses [15]. Antibiotics should be reserved for situations in which bacterial superinfections are suspected. Besides, the shortages of oxygen Although not proven, hypoxia may exacerbate damage of tissue partially infarcted by angioinvasion [15]. A final possible reason for the surge in post-COVID Mucormycosis is the unhygienic delivery of oxygen or low-quality tubing system to these patients at the hospital ICUs, the oxygen cylinders with unclean masks or using contaminated/tap water in humidifiers and prolonged usage of same mask for more than two patients [15].

Although COVID-19–associated Mucor mycosis isn't common [16], an emerging report from the world for the importance of considering this infection. Most of the COVID-19 patients did not have neither a sputum fungal evaluation at the start of their treatment, nor a follow up chest HRCT scan, which could enable the detection of fungal characteristics early and thus improving the outcomes. Because of increasing incidence of superimposed fungal infection, sputum fungal evaluation and CT scan should be considered as a useful tool in this pandemic. The presence of more than 10 nodules with pleural effusion and reverse halo sign in a covid-19 patients HRCT favors the diagnosis of pulmonary Mucormycosis infections [19]. Another differential diagnosis in the patient who developed hemiplegia and aphasia is that the clinical picture is caused by thrombosis due to covid-19 induced hypercoagulable state. Acute ischemic stroke (AIS) is a known neurological complication in patients with acute COVID-19 infection. (18, 19) The mechanism of AIS in COVID-19 patients has been postulated to be secondary to an associated hypercoagulability (20). Hypercoagulability due to SARS-CoV-2 virus is most likely the result of the profound COVID-19 inflammatory response and endothelial activation/damage [21]. The most common coagulation abnormalities are an elevated levels of fibrinogen and D-dimer, often with mild thrombocytopenia [22, 23]. Elevated D-dimer has been associated with a higher mortality rate. Thrombocytopenia is mild (a platelet counts of 100–150 ×109/L). Thrombocytopenia can also be caused by drugs such as Heparin. Heparin induced thrombocytopenia has been estimated to occur in 0.1–5% of patients receiving therapeutic doses of heparin [24-26].

Conclusion

We recommend that any patient with severe COVID-19 infection who is admitted to the ICU and has risk factors for fungal infection be treated as having a probable fungal infection during this pandemic, until proven otherwise. Empirical antifungal treatment should be initiated promptly, as superimposed fungal infections in COVID-19 patients are associated with significantly higher mortality. Once pulmonary fungal infection is diagnosed, other organs, particularly the brain and paranasal sinuses, should be thoroughly examined both clinically and radiologically, as these areas are commonly affected by fungal species. Limitation of the study: The imaging features of the CNS CT scan could not be included due to the patient's hypotension and worsening condition.

References

- Cevik, M., Kuppalli, K., Kindrachuk, J., & Peiris, M. (2020). Virology, transmission, and pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2. BMJ, 371:m3862.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Arastehfar, A., Carvalho, A., van de Veerdonk, F. L., et al. (2020). COVID-19 associated pulmonary Aspergillosis (CAPA)—From immunology to treatment. J Fungi (Basel), 6(91).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Dubey, R., Sen, K. K., Mohanty, S. S., et al. (2022). The rising burden of invasive fungal infections in COVID-19, can structured CT thorax change the game. Egyptian Journal of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, 53:18.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Cornely, O. A., Alastruey-Izquierdo, A., Arenz, D., et al. (2019). Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of mucormycosis: An initiative of the European Confederation of Medical Mycology in cooperation with the Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium. Lancet Infectious Diseases, 19:e405-e421.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Zurl, C., Hoenigl, M., Schulz, E., et al. (2021). Autopsy proven pulmonary mucormycosis due to Rhizopus microsporus in a critically ill COVID-19 patient with underlying hematological malignancy. J Fungi (Basel), 7(88).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Rudramurthy, S. M., Hoenigl, M., Meis, J. F., et al. (2021). ECMM/ISHAM recommendations for clinical management of COVID-19 associated mucormycosis in low- and middle-income countries. Mycoses, 64:1028-1037.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Elinav, H., Zimhony, O., Cohen, M. J., Marcovich, A. L., & Benenson, S. (2009). Rhinocerebral mucormycosis in patients without predisposing medical conditions: A review of the literature. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 15:693-697.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Roden, M. M., Zaoutis, T. E., Buchanan, W. L., Knudsen, T. A., Sarkisova, T. A., Schaufele, R. L., Sein, M., Sein, T., Chiou, C. C., Chu, J. H., et al. (2005). Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: A review of 929 reported cases. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 41:634-653.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Skiada, A., Pagano, L., Groll, A., Zimmerli, S., Dupont, B., Lagrou, K., et al. (2011). Zygomycosis in Europe: Analysis of 230 cases accrued by the registry of the European Confederation of Medical Mycology (ECMM) Working Group on Zygomycosis between 2005 and 2007. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 17:1859-1867.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Scheckenbach, K., Cornely, O., & Hoffmann, T. K. (2010). Emerging therapeutic options in fulminant invasive rhinocerebral mucormycosis. Auris Nasus Larynx, 37:322-328.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Vairaktaris, E., Moschos, M. M., & Vassiliou, S. (2009). Orbital cellulitis, orbital subperiosteal, and intraorbital abscess. Report of three cases and review of the literature. Journal of Cranio-Maxillo-Facial Surgery, 37:132-136.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Gillespie, M. B., & O'Malley, B. W. (2000). An algorithmic approach to the diagnosis and management of invasive fungal rhinosinusitis in the immunocompromised patient. Otolaryngologic Clinics, 33:323-334.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Werthman-Ehrenreich, A. (2021). Mucormycosis with orbital compartment syndrome in a patient with COVID-19. American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 42:264.e265-264.e268.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Dos Reis Neto, E. T., Kakehasi, A. M., de Medeiros Pinheiro, M., Ferreira, A., et al. (2020). Revisiting hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine for patients with chronic immunity-mediated inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Advances in Rheumatology, 60:32.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bhogireddy, R., Krishnamurthy, V., Jabaris, S. L., Pullaiah, C. P., Manohar, S. (2021). Is mucormycosis an inevitable complication of COVID-19 in India? The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases, 25(3):101597.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Hughes, S., Troise, O., Mughal, N., & Moorse, L. S. P. (2020). Bacterial and fungal coinfection among hospitalized patients with COVID-19: A retrospective cohort study in a UK secondary-care setting. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 27:1147.e1-1147.e5.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kumari, A., Rao, N. P., Patnaik, U., Tevatia, M. S., Thakur, S., Jaydevan, J., & Saxena, P. (2021). Management outcomes of mucormycosis in COVID-19 patients: A preliminary report from a tertiary care hospital. Medical Journal Armed Forces India, 77(S2):S289-S295.

Publisher | Google Scholor - McGonagle, D., O'Donnell, J. S., Sharif, K., Emery, P., & Bridgewood, C. (2020). Immune mechanisms of pulmonary intravascular coagulopathy in COVID-19 pneumonia. Lancet Rheumatology, 2(7):e437-e445.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bikdeli, B., Madhavan, M. V., Jimenez, D., Chuich, T., Dreyfus, I., Driggin, E., et al. (2020). COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: Implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up: JACC state-of-the-art review. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 75(23):2950-2973.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Helms, J., Tacquard, C., Severac, F., Leonard-Lorant, I., Ohana, M., Delabranche, X., et al. (2020). High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: A multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Medicine, 46(6):1089-1098.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Wool, G. D., & Miller, J. L. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 disease on platelets and coagulation. Pathobiology, 88:15-27.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Connors, J. M., & Levy, J. H. (2020). COVID-19 and its implications for thrombosis and anticoagulation. Blood, 135(23):2033-2040.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Levi, M., Thachil, J., Iba, T., & Levy, J. H. (2020). Coagulation abnormalities and thrombosis in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Haematology, 7(6):e438-e440.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Chaudhry, R., Wegner, R., Zaki, J. F., et al. (2017). Incidence and outcomes of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia in patients undergoing vascular surgery. Journal of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Anesthesia, 31:1751-1757.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Solanki, J., Shenoy, S., Downs, E., et al. (2019). Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and cardiac surgery. Seminars in Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, 31:335-344.

Publisher | Google Scholor - McGowan, K. E., Makari, J., Diamantouros, A., et al. (2016). Reducing the hospital burden of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: Impact of an avoid-heparin program. Blood, 127:1954-1959.

Publisher | Google Scholor